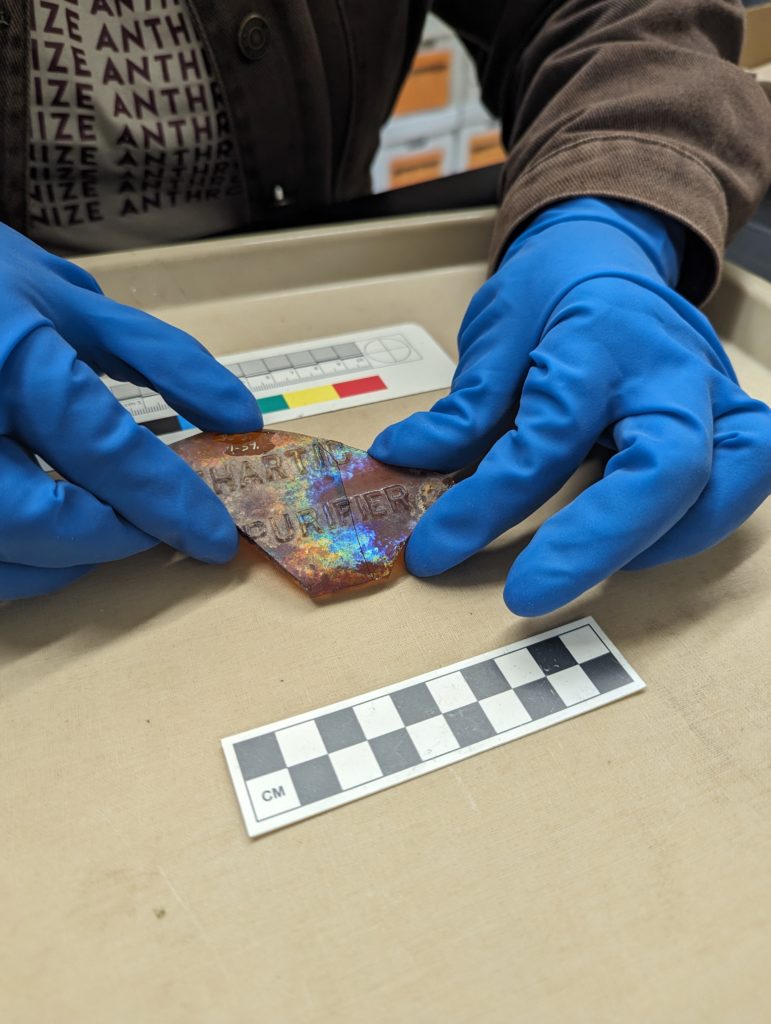

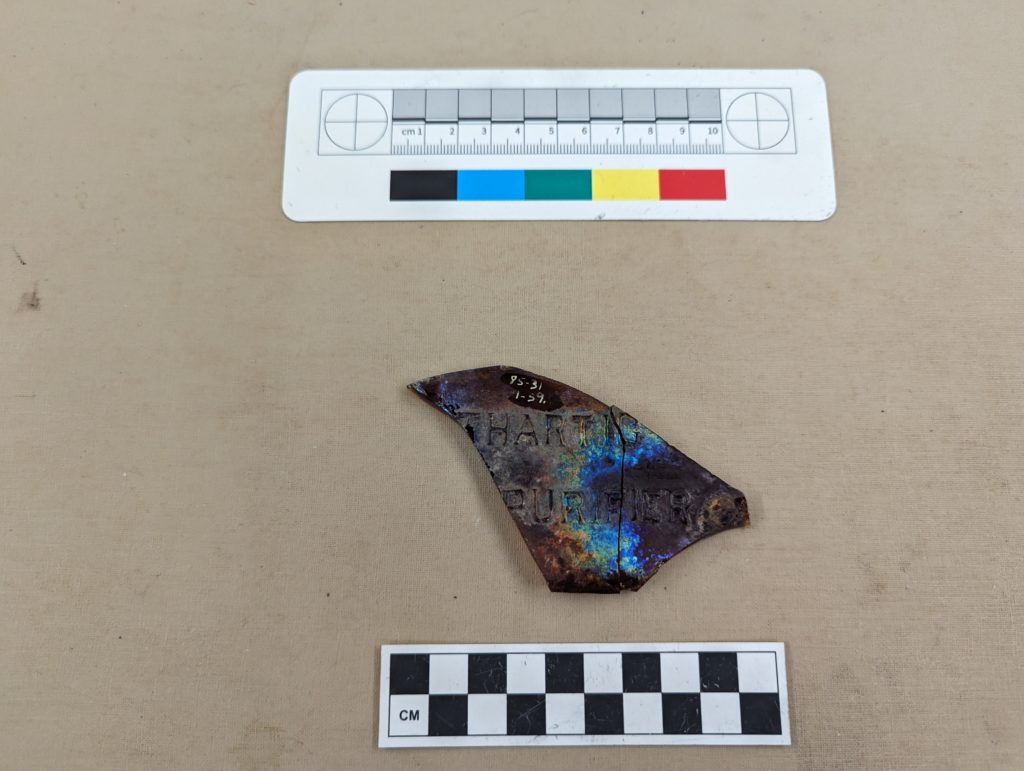

Lots of bottle fragments in our collection have bits of writing on them, but how do you go from a partial inscription to figuring out what they mean? Transcribing embossed marks (words on a bottle that were formed through machine molding) requires three skills: archival research, imagination, and curiosity. This example (one of Alana’s favorites) had the letters “…THARTIC” and “PURIFIER”. With a bit of guesswork, we could tell that it probably had originally said “CATHARTIC” and “BLOOD PURIFIER”. With this information we could either try a Google search or turn to our trusty copy of The Bottle Book by Richard Fike which catalogs most 19th century American medicine bottles. Sure enough, that showed us that our bottle matched Lash’s Kidney and Liver Bitters: the Best Cathartic and Blood Purifier.

Of all the hundreds of different patent medicine products, Lash’s is one of the few which we know quite a bit about. Three articles (see below) by Michael Torbenson, Jonathan Erlen et al. lay out the history of the company, its advertising strategy, and the contents of Lash’s Bitters which was produced under several different names between 1884 and the 1960s.

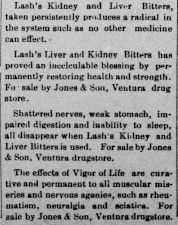

Ventura Weekly Democrat, Volume XI, Number 22, 12 January 1894. Courtesy of the California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside, http://cdnc.ucr.edu

Bitters, an alcohol product infused with bitter plants, were first sold as medicines. As you can tell from the name, Lash’s Kidney and Liver Bitters was a laxative specifically aimed at treating illnesses of the kidneys and liver but also promised relief from “Biliousness, Malaria, Dyspepsia, Indigestion, Chills and Fever, Sick Headache, Sour Stomach, Neuralgia, Pain in Back” (Torbenson et al. 2000: 59). Over time, however, Torbenson et al. (2001) have shown that the advertising changed to focus on the product’s alcohol content and began to market it primarily to men drinking in saloons, probably as a reaction to changes in regulation.

Notice how the advertising has shifted away from medicine and towards men’s social drinking. Public domain, courtesy of the National Library of Medicine resource.nlm.nih.gov/101702454.

By testing the contents of a sealed bottle of Lash’s Bitters from around 1918, Torbenson et al. (2000) found that it had a high alcohol content (19.2% ethanol, similar to fortified wine, as well as methanol), no evidence of the advertised laxative ingredient, and toxic amounts of lead. That helps to explain why greater regulation of patent medicines was needed!

Our fragments of a bitters bottle, and another, slightly later whole bottle, point to the popularity of Lash’s bitters and similar products for self-medicating at a time when visiting a doctor was expensive and not necessarily much more helpful. In the Market Street Chinatown, inhabitants combined Traditional Chinese Medicine with patent medicines and compounded medicines from pharmacies to treat themselves.

More information:

Torbenson, B.C., J. Erlen & M.S. Torbenson. 2001. Lash’s Bitters: From the Bathroom to the Barroom. Pharmacy in History 43. American Institute of the History of Pharmacy: 14–22.

Torbenson, M. & J. Erlen. 2003. A Case Study of the Lash’s Bitters Company—Advertising Changes after the Federal Food and Drugs Act of 1906 and the Sherley Amendment of 1912. Pharmacy in History 45. American Institute of the History of Pharmacy: 139–49.

Torbenson, M., R.H. Kelly, J. Erlen, L. Cropcho, M. Moraca, B. Beiler, K.N. Rao & M. Virji. 2000. Lash’s: A bitter medicine: Biochemical analysis of an historical proprietary medicine. Historical Archaeology 34: 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03374313.

Wills, M. 2021. The Bitter Truth About Bitters. JSTOR Daily. July 9. https://daily.jstor.org/the-bitter-truth-about-bitters/.