As I welcomed a new, massive roll of Ethafoam into Dr. Voss’s lab at Stanford last week, I knew it was time to share our progress with all the friends and partners of the Market Street Chinatown Project. I started working with the collection in September, organizing and recording previously catalogued materials in preparation for curation and use by future researchers. After many hours of sorting and resorting, close to two dozen boxes are ready to be packed in stable, protective packaging and to have their content inventories entered into our artifact database. The goal of this stage of the project is to provide an organizational system which can help track the progress of cataloguing, and within which each artifact can be relocated for further analyses. While working through the materials I was impressed by the diversity of the collection – with ceramics of Asian and European manufacture ranging from plain, thick and utilitarian to refined and decorative; bottles from an array of commercial products including hair tonic, bitters, sauces, and alcoholic beverages; and a fascinating combination of small objects such as buttons, doll parts, gaming pieces, and toothbrushes. Student researchers have already made a great contribution to our understanding of the collection, but it seems that there are many more potential research projects waiting in these boxes!

The next stage of my work with the Market Street Chinatown collection is to sort and catalog faunal remains from the 1985, 1986, and 1991 excavations and prepare a portion for specialized zooarchaeological analysis. In the few boxes I’ve sorted so far, the many bags of large mammal, bird, and fish bones hint at the wealth of dietary information they can provide. One type of faunal material that I hadn’t seen in a collection before is cuttlefish bone, the white, spongy, layered fragments from the internal “shell” of a kind of cephalopod. Other mollusk shells, from oysters and mussels, add to the potential information about residents’ use of marine resources.

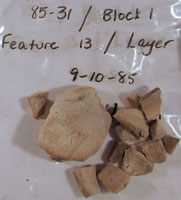

Featured Artifact

This portion of an aqua-colored, post-molded bottle with embossed panels on either side reading “…NNEWELL & CO” and “BOSTON” is a great example of how one artifact can be a key for interpreting others of its kind. In her glass cataloging work, Jessica found several fragments of distinctive deep aqua, octagonal bottles with concave panels. None of these fragments had embossed labels indicating the containers’ former contents, though, so they couldn’t be attributed to a product or manufacturer. When I found this bottle among the 85-31 “small finds,” I knew it could help us with those other fragments. A bit of research using Bill Hunt’s Medicine Bottle Glass Index [http://www.nps.gov/history/mwac/bottle_glass/index.html] helped to fill out the manufacturer’s name to “J.L. Hunnewell &Co.” of Boston, and a search of the Society for Historical Archaeology’s Historic Bottle Website [http://www.sha.org/bottle/] gave us the lead that these might have held mustard or other seasonings. More research into Hunnewell & Co.’s line of products and bottle styles may help us to refine the identification.