I’ve been busily digging through the glass again after coming back from the winter break and, as a keen preserver and jam-maker, I was intrigued by two fragments in particular.

Wax Seal Glass Jars

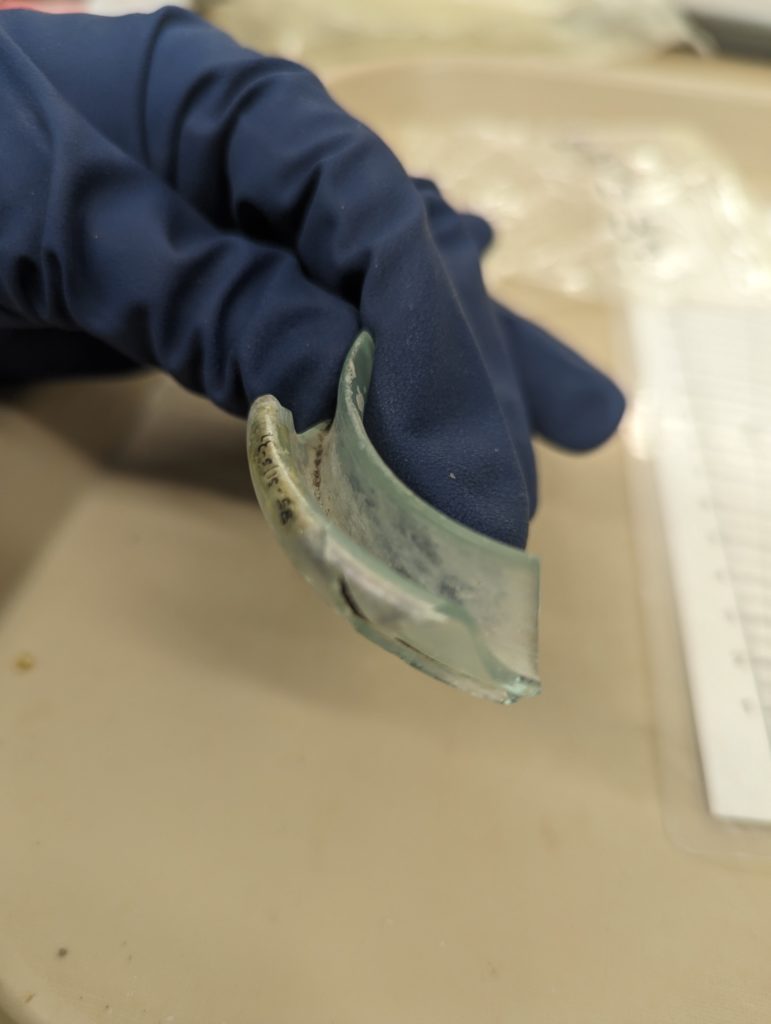

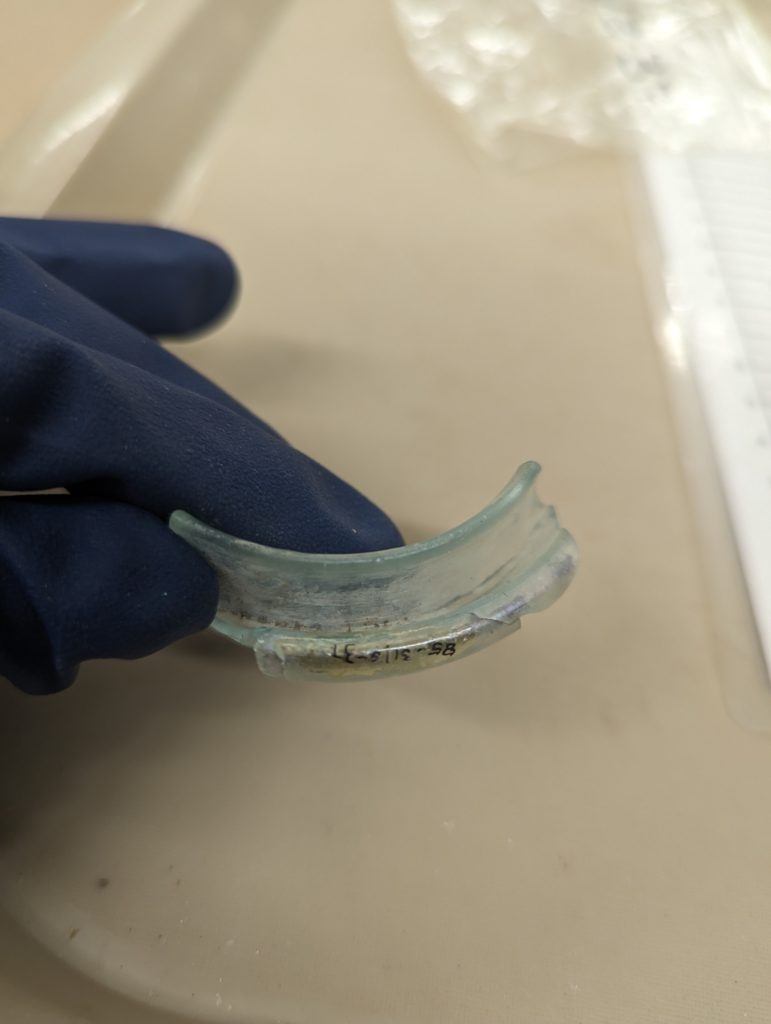

The first one looks like this:

It’s part of the rim of an aqua canning jar with what’s called a groove ring wax seal finish. The finish is the part around the opening of a glass vessel and particular types of finish are associated with particular types of closures. An external thread finish, for example, is commonly used today on jars which have screw on metal or plastic lids.

Since finishes can be quite distinctive, it is sometimes possible to use them to infer the date or contents of a glass bottle or jar. In this case, we know that wide-mouthed vessels with a groove ring wax seal finish are canning jars, sold either for home preserving or sometimes with contents inside them.

The groove ring wax seal finish was closed by putting melted wax in the groove and then placing a metal or glass lid over the top of the jar and pushing it into the wax to create a seal. To see some whole examples, take a look at the canning jars section of the SHA Bottle Identification Website.

This type of jar was in use for much of the nineteenth-century and even into the twentieth century, but they were most popular from the 1850s to the 1870s which means there is a good chance that this jar was used by someone living at the Chinatown.

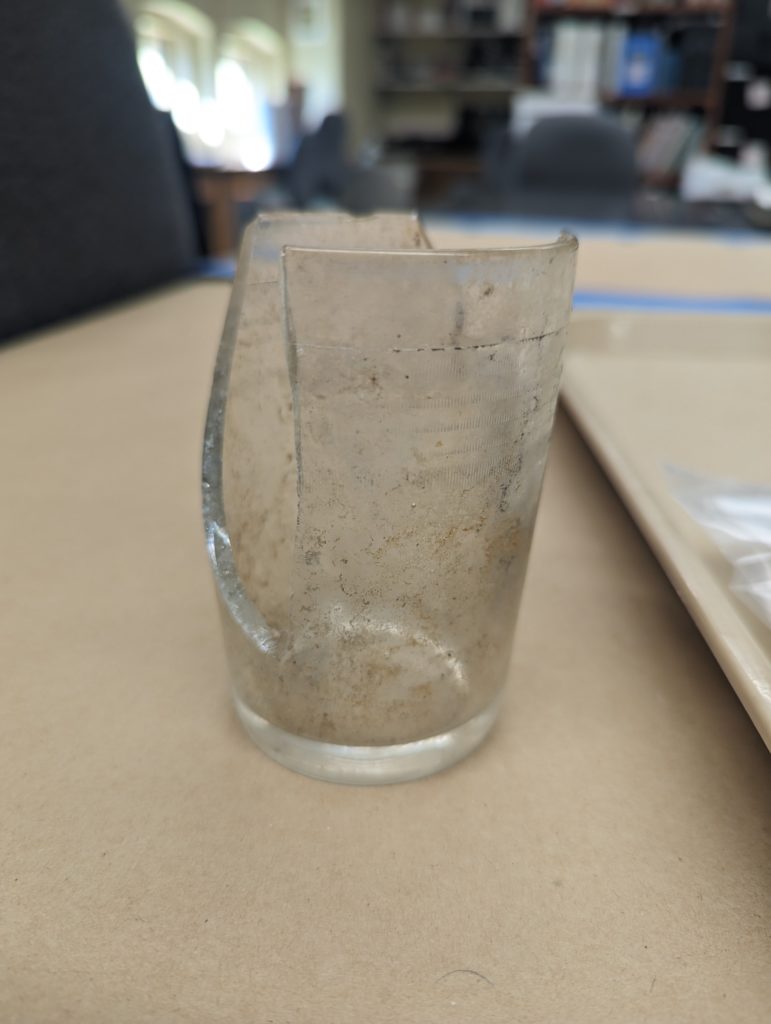

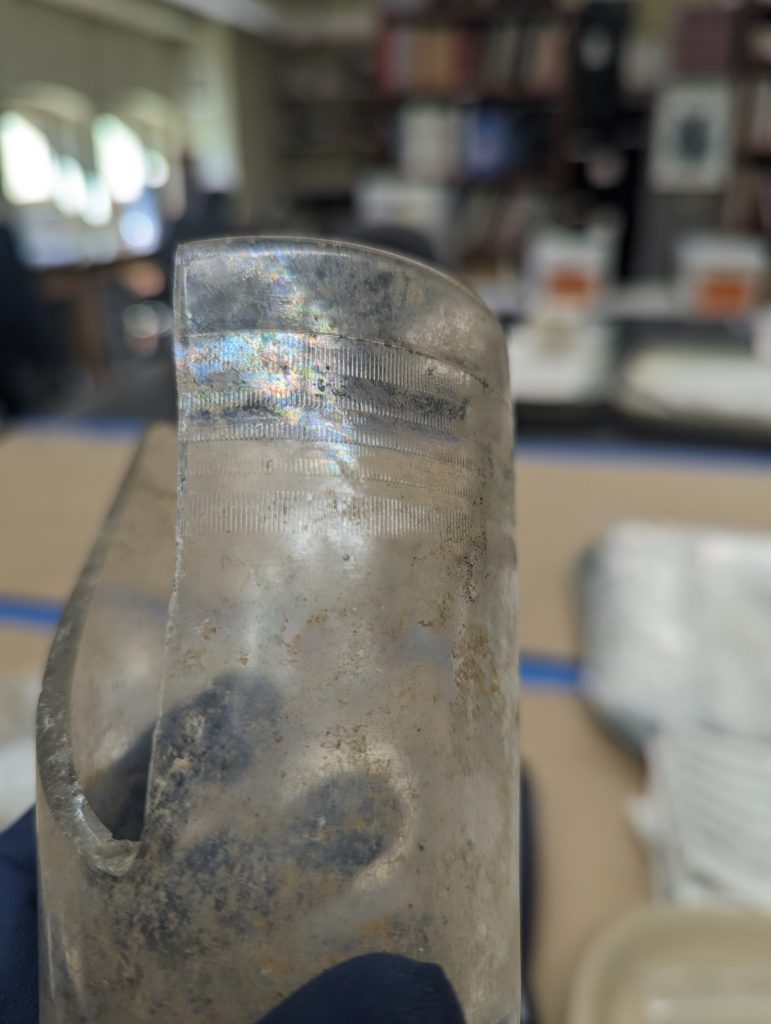

Packer’s Tumblers

When I was little I remember visiting friends’ houses and being fascinated by plain drinking glasses decorated with colorful cartoon characters. Their lives as drinking glasses was actually a reincarnation; the jars were sold originally for their contents. Filled with jam or peanut butter or other spreads, the jars were designed to be attractive enough for pocket-conscious consumers to repurpose as tumblers. It’s not hard to imagine kids trying to finish off the last of the grape jelly to be able to collect the next character in the lineup!

The earliest ‘packer’s tumblers’, as they’re known by archaeologists, were more utilitarian in design with no decoration or maybe simple flutes or a few lines of fine vertical ridges beneath the rim. These vertical lines are a sign that the jar used a particular type of lid called an Anchor Cap closure which was introduced in the 20th century.

In the Market Street Chinatown Archaeology Project collection, I’ve just found our first packer’s tumbler which is a little bit unusual with five lines of these vertical ridges (1-3 lines is more common). Probably in use between 1908 and the 1960s, this jar reminds us of the site’s history after the catastrophic fire in the Chinatown and points to a gradual shift from home-preserving to purchasing packaged food products.

For more information and other examples of this type of jar, check out this post on the MSU Campus Archaeology Program’s blog called Not Ready for this Jelly Juice Glass or the examples of packer’s tumblers from the Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland site.